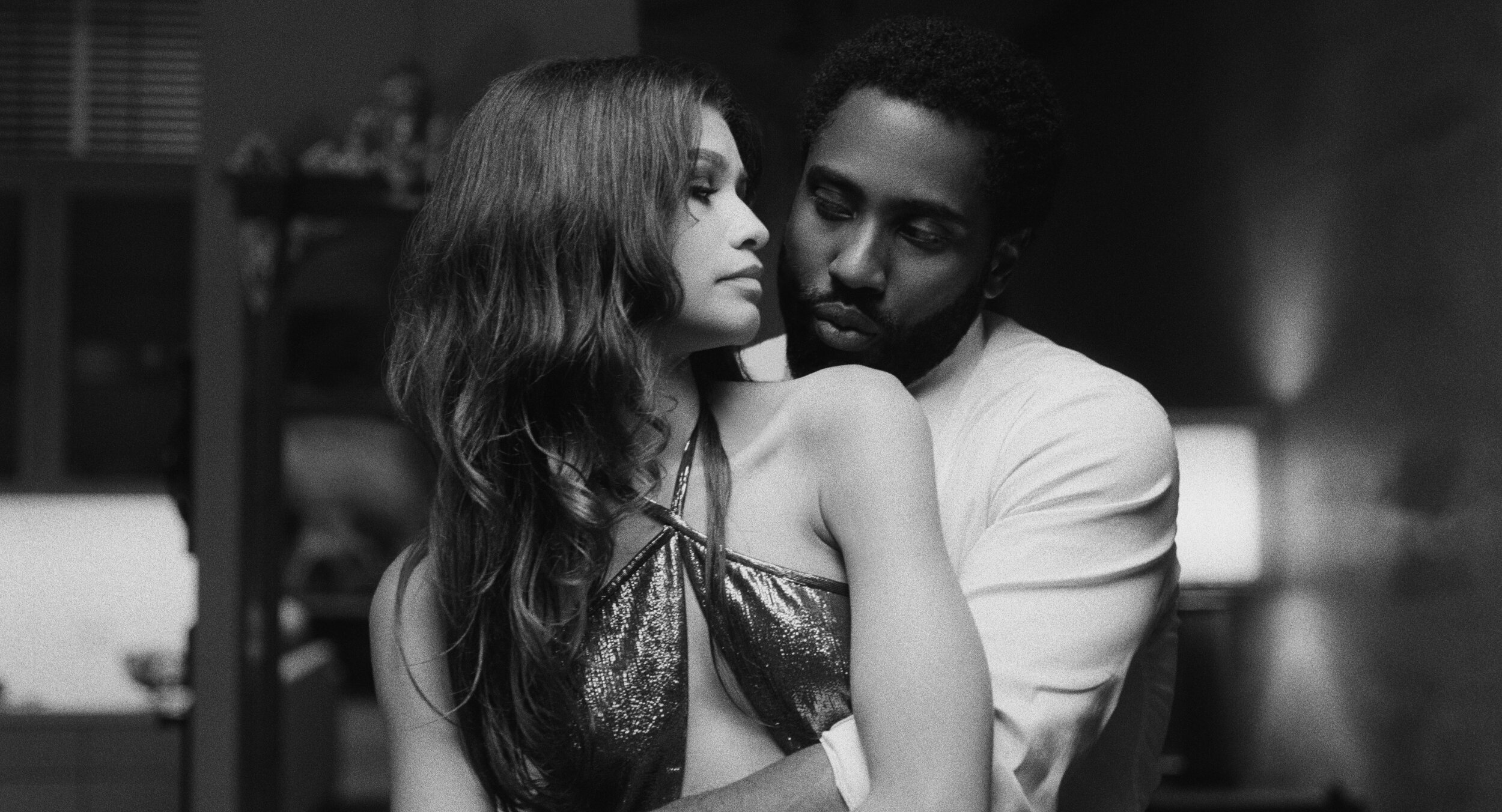

'Malcolm & Marie' Review

R: Pervasive language and sexual content

Runtime: 1 Hr and 46 Minutes

Production Companies: Little Lamb, Fotokem

Distributor: Netflix

Director: Sam Levinson

Writer: Sam Levinson

Cast: Zendaya, John David Washington

Release Date: February 5, 2021

A filmmaker (Washington) and his girlfriend (Zendaya) return home following a celebratory movie premiere as he awaits what's sure to be an imminent critical and financial success. The evening suddenly takes a turn as revelations about their relationships begin to surface, testing the strength of their love.

It’s about damn time John David Washington got to let loose in a film that showcases his range as an actor. That man has worked with the likes of Christopher Nolan and Spike Lee, yet he never got a chance to shine and often got overshadowed by his supporting cast. Luckily, Malcolm & Marie is just Washington and Zendaya leading the picture as equals, so he gets to demonstrate a different, more dominant side of his talents. He plays an emotionally manipulative character, going through the motions like a Sour Patch Kid where he can be both sour and sweet. In this toxic relationship, Malcolm is the egocentric, shallow, aggressive partner who calls the shots and John David Washington does a great job portraying such an incorrigible character.

While this is John David Washington’s first standout performance, he is still slightly outshined by the tour de force that is Zendaya. If Washington is jumping through his first hoop in this film, then Zendaya is jumping through multiple rings of fire… and she makes it through without a scratch. Malcolm & Marie is essentially one prolonged argument based around Marie feeling some type of way towards her older director boyfriend who didn’t thank her in his opening speech at his movie’s premiere. From the get-go, Marie’s anger and resentment are validated, but the way Zendaya delivers this performance is bone-chilling. From Marie’s cold glares at Malcolm to the dry, sarcastic tone of her voice, and even the way she reacts to his over-the-top angst and cruelty, Zendaya’s acting is so otherworldly that whenever the film took me out, her performance reeled me back in. Because Marie is doing the heavy lifting in their toxic relationship, Zendaya has more material to work with and she delivers ample lengthy monologues as best as she can.

From a technical standpoint, the original score by Labrinth is great. I really like the choice of psychedelic jazz to complement the heated moments of tension between the two leads and the brief quiet moments as their aggression dies down… only for somebody to trigger another argument again. Also, the cinematography by Marcell Rév is absolutely stunning. Rév has worked as a DP with director Sam Levinson on projects like Assassination Nation and Euphoria. While those projects feature a glossy, in-your-face style, the visual presentation is personable and intimate in shot composition alone.

Throughout the dialogue-heavy lovers’ quarrels, the conversations that lead towards heated arguments hit a variety of topics: drug abuse, recovery, and the Hollywood industry itself, specifically the current landscape of film criticism. They mostly discussed these topics while reiterating the words “authenticity” and “experience”. I find it ironic that a movie that overuses those words still comes off as completely inauthentic to the Black experience. I couldn’t help but overhear the sound of Sam Levinson constantly veiling his fragile white male ego through his Black characters, airing out his petty personal grievances towards a specific film critic in such a shallow and mean-spirited manner.

Within the first ten minutes, the film name-drops some of the most popular and mainstream publications in regards to the reception of Malcolm’s movie as he happily touts, “The white guy from Indiewire loved it. The white guy from Variety loved it.” It’s rather ambiguous at first because, while many can say journalist David Ehrlich is THE white guy at Indiewire, there are just so many white guys at Variety. That ambiguity quickly withers away when Malcolm says, “The white woman at the LA Times.” Now, it’s worth noting that there is indeed one white woman who is a contributor for the LA Times. Her name is Katie Walsh and a few years back she published a well-written (but negative) review of Levinson’s Assassination Nation. I, for one, genuinely liked Assassination Nation, but I did criticize the way it projects a feminist message through a sexualized and exploitative male gaze on high school-aged girls. And guess what? Walsh’s review criticized the film for doing exactly that. That being said, Levinson’s screenplay focuses on taking extensive, relentless, mean-spirited potshots at Walsh that are deep-rooted in blatant pettiness with the subtlety of Emmerich’s jabs at Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel with Godzilla (1998).

The film creates a non-existent narrative by dubbing her as a “Karen” (which isn’t even used in the right context). Now, I’ve personally experienced my fair share of actual racist white female critics in this field, especially within the past year. I’m not trying to justify any problematic critic’s actions, but when an unproblematic, skilled writer who articulates her opinions like a professional is being attacked out of pettiness, it becomes an uncomfortable situation. As a Black film critic, that discomfort quickly turned repulsion as Levinson — a white male filmmaker — used Black characters to channel his personal grievances towards a writer with an occupation in film criticism, devaluing her work simply because she had understandable complaints about Assassination Nation.

I will always welcome an insightful argument about the elitist and white-dominated state of film criticism, especially from a non-white perspective and/or one that isn’t so mined from the overdone “fuck critics” mentality that Hollywood loves to perpetuate in films. Levinson’s argument becomes invalid almost immediately as it comes from a self-indulgent, mean-spirited place of scorn. Meanwhile, he’s a white male filmmaker who thrived off of nepotism as the son of an esteemed filmmaker. While Malcolm and Marie go back and forth, referencing this “white woman from the LA Times” in a hostile manner, all you hear is the voice of Sam Levinson in a surreal Anomalisa-esque way.

Based on the way Malcolm is written and how he articulates his thoughts as a Black filmmaker in Hollywood, Levinson must have a narrow-minded view of Black filmmakers and film criticism. While yes, Black filmmakers get frustrated by the reception from white critics — who often critique their works by comparing them to those of other popular Black filmmakers — they don’t get completely hung up on it, nor would they go for an over-the-top, one-dimensional, self-indulgent rant that shits on the profession as a whole. Malcolm & Marie has much to say about film criticism being so white and the white perception of Black art, selfishly thinking it's doing us a favor or adding to a conversation that has already been discussed too often. Never for a moment does it address or seek the perspective of Black voices within film criticism. The film acts as if non-white — and, more importantly, Black critics — simply don’t exist. That’s why Malcolm never felt like an authentic Black filmmaker or character to me. There are so many things that aren’t touched upon, including those that are so personal to our experiences as Black critics who often interact with Black artists. Many Black filmmakers today look towards their demographic and read critiques from Black writers. This film would make sense if it had come out prior to Rotten Tomatoes’ 2018 diverse pool change, but so much has changed since then. At this moment in time, Black filmmakers don't give a shit about white reviews to that extent. Black filmmakers find their audiences and their critics and latch onto them, but the movie doesn't address that at all. Malcolm is a caricature of a Black filmmaker that could only have been written by a white man.

Even if I exclude the conversation of race, if you've never taken a dip in the ocean then of course a pool seems deep. How can you talk about the ocean of film criticism when you’ve never even been to the pool? You don’t know the importance of a relationship between an up-and-coming filmmaker and a journalist who understands art — one who earned their position in their profession, and can help champion your movie.

When Levinson’s tasteless conversation about film criticism finally gets to the meat of the couple’s dispute, which is rooted in Malcolm forgetting to thank his girlfriend, Marie, the muse who inspired his movie (something that was based on real events where Levinson forgot to thank his wife at the premiere of Assassination Nation), the film is still an insufferable mess. The incompatibility of the titular characters is so noticeable that both partners are borderline grating, especially Malcolm. Malcolm is shallow, manipulative, and verbally abusive towards his girlfriend, who is vocal about her (valid) feelings of not being acknowledged at his premiere. His ego-driven responses escalate their conversations into arguments as he insults her in such an irredeemable, cruel manner. While the lust for his younger girlfriend is present, the love is never felt. Though you immediately side with Marie from the get-go, the film tries to shift in favor of Malcolm’s argument when he is clearly depicted as an excessively abusive and shallow person. The longer their exhausting bouts continue, the more you get frustrated with Marie, constantly questioning why she didn’t dump his ass before he even completed his movie, which is about her past as a drug addict.

I know the year just started, but I’ve already had the opportunity to see a handful of 2021 movies. I’m going to be completely blunt when I say that Malcolm & Marie is one of the most frustrating movies I’ve had to sit through in a long time. While the performances and the technical aspects help maintain the entertainment value of the film, the obnoxious sound of Sam Levinson’s shallow screenplay, full of unnecessary childish vulgarities, frustratingly mean-spirited dialogue, and hollow takes on a field he doesn’t value defeat the sound of his inauthentic Black caricatures. All you hear throughout the film is the deafening scream of a fragile white male ego.

Stream Radha Blank’s The 40-Year-Old Version if you want an AUTHENTIC story about a Black woman, directed and written by a Black woman, navigating the entertainment industry with nuance and relatable realism.